If there was ever a physics rockstar, Richard Feyman is him. One of the most brilliant physicists, he gained notoriety due to his charismatic and fun teaching style. Six Easy Pieces is his book based on the introductory courses to physics for the freshmen at Caltech. It’s said to be a very approachable introduction to a complex field, even for people without background. Like me.

This week I’m reading the book, so I’ll try to simplify the key elements here. I’ll start with the two first chapters, which are the basics.

1. Atoms in motion

Everything is made of atoms.

There is nothing that living things do that cannot be understood from the point of view that they are made of atoms acting according to the laws of physics

Atoms are small. They are between 30 and 300 pm (trillionths of a meter), or between 0.3 and 3 ångströms. The relative size of an atom to the apple it’s a part of, is that of the apple itself to the earth.

- Atoms always move. They can move more or less, but they always move.

- Atoms always have energy. They can have more or less, but they always have energy.

- Atoms attract each other when close, but if you try to squeeze them they repell.

Everything depends on how these atoms interact with each other.

Water is an easy way of illustrating this point. Two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom combine, forming a molecule. That molecule moves and vibrates a bit. If you put heat into the equation, those molecules will have more (kinetic) energy, and move more. When they move more, they take up more space and separate. They start moving in the air and go everywhere, evaporating. If you take energy away (by freezing it), the molecules move less, and get compact, and you get ice. That’s how liquid, solid and gases work on an atomic level.

Then there’s atomic processes, which are molecules changing places.

For example, this happens on the surface of water. Water molecules always move, and from time to time, one moves to much and ‘flies’ away. In perfect conditions, other nearby water molecules take their place. But you can make more water molecules leave (by heating, thus giving more movement). You can also reduce the number of water molecules joining again, by drying the air. Now you know why hot soup cools at room temperature. And why it cools faster when we blow.

Another process is crystals dissolving. Crystals are formed by ions – an atom that has either gained or lost electrons. We’ll get to electrons later.

Water molecules are like the US; polarized. That means, it’s formed by a negative side (oxygen) and a posititve side (hydrogen). That they are negative or positive has nothing to do with them being bad or good, and everything to do with the fact that one has a negative electrons charge (-2) and the other a positive electrons charge (+1). Ions stick together due to their electrical charge, and they break when that electrical charge is messed with. What messes with the electrical charge is precisely the imbalance of the electrons from the water molecules. Some ions leave, some join. But when there’s more water molecules than ions around, more of these ions leave the structure than join. That’s why salt dissolves in water. But the ions are still there, so when there is more ions than water molecules around, the structure is build again. That why when drying seawater, once the water molecules evaporate, you’re left with sea salt.

And then we have the chemical reactions. Those are atoms switching combinations, forming new molecules. The electrons in atoms make them bond (or not) with other atoms. Since those processes involve energy, they will also affect the atoms nearby.

For example: Carbon attracts oxygen. Kind of like a magnet. So, when they join, they do so with a bang. Not a big bang, but a small bang. That small bang will create vibration all around it, making other atoms, or molecules, or ions, or whatever, vibrate. And what happens when molecules vibrate more? There’s more heat. That’s why processes that create CO2 (one carbon atom joining to oxygen atoms) give heat.

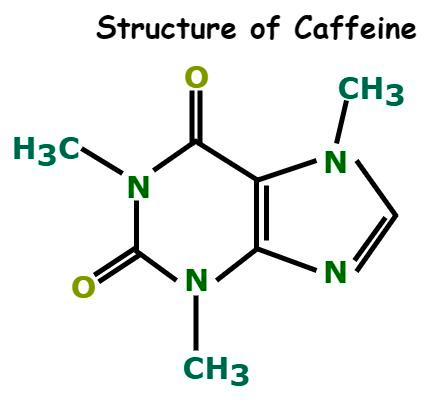

Atoms join to form molecules, and those molecules are expressed by chemical formulas. Here’s an example of how that looks like:

This doesn’t tell you or me anything, but physicists pretend they can understand how a molecule is formed with it.

2. Basic Physics

In the second chapter, Feynman goes into fundamental physics, which is described by the set of rules by which the games of the universe play. We don’t know all these rules, but by observing, investigating and calculating we can figure some of them out.

How can we know if these rules are correct? Well, in physics there’s three ways. The first one is if the rule is relatively easy and straight-forward, and we can check how the rules work by ourselves. The second one is by deriving other rules from the original rules. Third, by approximation. We might not understand why a specific phenomenon is happening, but we can understand that it is part of a larger thing that is happening.

The beauty (and difficulty) of physics is that we’re figuring out pieces of the puzzle as we go. And some don’t seem to fit at the beginning. Physicists try to solve the puzzle without knowing if the pieces form part of one big megapuzzle that explains everything, or if we’re doomed to forever use classes like heat, mechanics, optics, x-rays, gravitation, etc. that sometimes work together, and sometimes seem to be completely different.

Before 1920, things as we understood them, looked different. This is important to know, because the best way to explain what we know today comes from what we knew (or thought we knew) before 1920.

Feynman explains that the world was viewed as a 3D geometrical space, where things change in a medium called time and where the elements of the stage are called particles. Forces act on these particles, and all matter is formed from particles, including atoms. Pressure comes from the collision of atoms. Random internal motions are heat. Waves of excess density are sound.

And now we come to the part in which we finally explain what an electron is. You might remember from school biology (I didn’t) that atoms are formed by a positive nucleus at the center. Well, that nucleus is surrounded by electrons, which are negatively charged particles. Two other kinds of particles – protons and neutrons – form the nucleus itself. Protons are positively charged, neutrons are, as you can imagine, neutral. This all is important because the chemical properties depend on how many electrons are on the outside shell of an atom. Actually, the number of electrons make up the number of the element ,which makes up the number on the periodic table.

Here’s a picture I stole which illustrates this point (thank you, Pearson Education):

The existence of a positive charge creates the necessary conditions to create a force when a negative charge is introduced. This is how electric fields are made. There is two rules: 1. Charges make a field 2. Charges in a field have forces on them and move

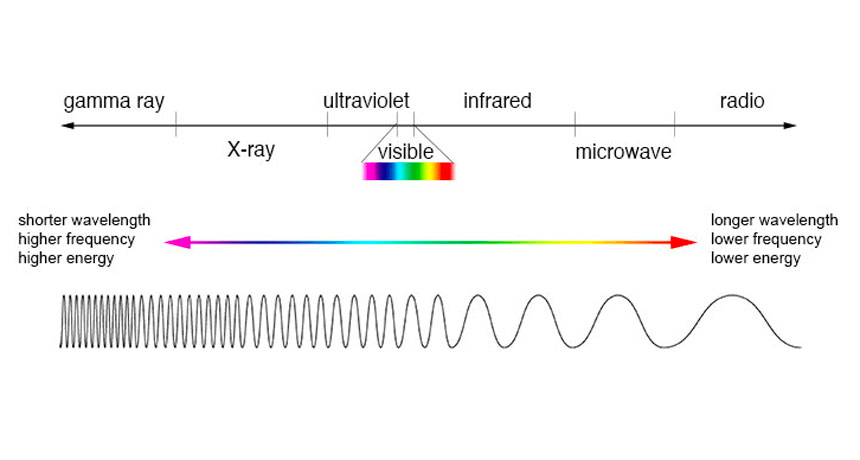

What’s the magic of electric fields? They can carry waves. Those could be radio waves, microwaves, infrared, (visible) light, ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays – but the general name is electromagnetic waves. These waves have frequencies (the up’s and downs of the waves), which differ basically in frequency of oscillation.

Alright, big step done. Let’s take a small pause, take a breath… And jump right into how things looked like after 1920.

Funnily enough, at higher frequencies, waves actually behave more like particles instead of waves. This behavior is explained by quantum mechanics. You remember stage, time, and the forces that consituted the play? Good, because you can now forget about that: the first thing that changed after 1920 was the view of space and time being separated. Instead, Einstein started saying that it’s actually one common phenomenon: space-time. And forces like gravitation are just a modification of space-time.

He kept on ruining things, and was now arguing against the rules of the motion of particles, contradicting Newton’s mechanical rules of “inertia” and “forces”. The main issue was that, until then, we thought that things behave on small scale like they behave on big scale. But no, no. They actually behave very differently, which is what makes physics so difficult – and for some people, apparently, all the more interesting.

With making physics difficult, what he means is that you need a lot of imagination because particles and atoms behave like nothing we know of or can see. That’s what makes it so challenging to describe physics.

For example, the notion that a particle has a definite location and speed is wrong. Like, wrong, wrong. There’s a rule in quantum mechanics that states that one cannot know both where something is and how fast it is moving. Which is totally contradictory to our human experience because we’re used to knowing both. You know where the table you sit on is, and you would know if it was moving.

Another thing we can’t do is predict exactly what will happen: what particle will act and do what and how much and when it will start and when it will stop and when it will move? We simply don’t know.

Alright, more confusing stuff: remember how particles generate waves, which are different to particles but sometimes act the same? Well, now we believe they actually behave the same, always. In fact, everything behaves the same way. There is no distinction between a particle and a wave. Quantum mechanics unifies the idea of waves and particles. And that new idea gives us a new view of electromagnetic interaction, and it brings a little present; a new particle in addition to the electron, proton, and neutron. Let me introduce you to the photon. Photons are fundamental subatomic particles that carry the electromagnetic force.

This new relationship between the electrons and photons is called quantum electrodynamics, which is what Feynman calls the greatest success so far in physics. All known electrical, mechanical, and chemical laws can be explained by quantum electrondynamics: the collisions of billiard balls, the motions of wires in magnetic fields, the specific heat of carbon monoxide, the color of neon signs or the density of salt.

That’ how physicists arrived at a theory that, on the level of atoms and particles explains, most accurately what is happening.

Once quantum electrodynamics was established as a discipline, many new findings came out of it. One of those; for each particle, there is an antiparticle (except those particles that are somehow their own antiparticle). For every electron there is a positron, which has the same mass and opposite charge. There’s also antiprotons and antineutrons, the latter sounding more like an adjective describing my friends political views.

Back to nuclei and protons. Nuclei are held together by enormous forces, which explains why atomic bomb explosions are so much more brutal than TNT explosions: the latter has to do with changes of the electrons on the outside of atoms, and the former has to do with changes in the nuclei. The ‘nuclear force’ is responsible for this, binding together neutrons and protons – it falls under the general concept of ‘strong interaction’ or ‘strong force’.

Then, Feynam goes into some detail about the known particles to that date, and explains the categories under which they can fall:

- Hadrons, which will have strong force and interact on nuclear level. They are divided in in Baryons or Mesons.

- Leptons, which don’t operate on nuclear level.

One last thing: there is the possibility for a particle to have zero mass, which somehow means that it cannot be at rest. This doesn’t make any sense now, but the theory of relativity should help understanding that.

Up to this date, we’re still discovering new particles and their properties, but this is the basis on which these foundings are made.

We will continue with the remaining chapters some other day.

Leave a comment